Roughly 1,100 to 800 million years ago, lava was deposited in the easternmost portion of West Virginia, forming the Catoctin Greenstone. About 800 million years ago, a narrow trough began to form in eastern West Virginia, and an arm of the ocean entered this trough depositing sediment. This shallow sea transgressed westward over time and covered most of West Virginia by the end of the Cambrian Period. Marine deposition occurred throughout most of the Cambrian and Ordovician periods. During this time interval, most of the rocks exposed in Jefferson and eastern Berkeley counties and in scattered areas of southeastern West Virginia along the Virginia border were deposited. Rocks of the same age are found in deep borings throughout West Virginia. The oldest evidence of life found in West Virginia occurs in rocks of the Antietam Formation of Lower Cambrian age. The

Geologic Time Scale, as published by the USGS, shows age ranges for Cambrian, Ordovician, Devonian, etc.)

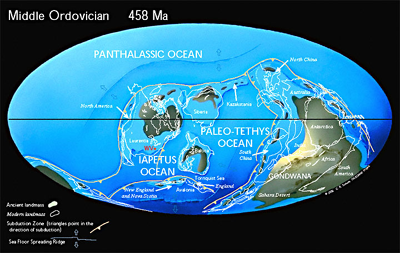

The three major mounatin-building episodes, or orogenies, recognized in the Appalachians were caused by a sequence of tectonic-plate collisions resulting in rapid subsidence events. The first, the Taconic Orogeny, occurred near the end of the Ordovician Period and formed a high mountainous area east of West Virginia. These highlands were the major source of sediment deposited during the subsequent Silurian Period and part of the Devonian Period. Both clastics, such as shales and sandstones, and carbonates, such as limestones and dolostones, were deposited in a mixed marine and nonmarine environment, with clastics predominating in the eastern part of West Virginia. Evaporites were deposited in northern West Virginia during the Late Silurian.

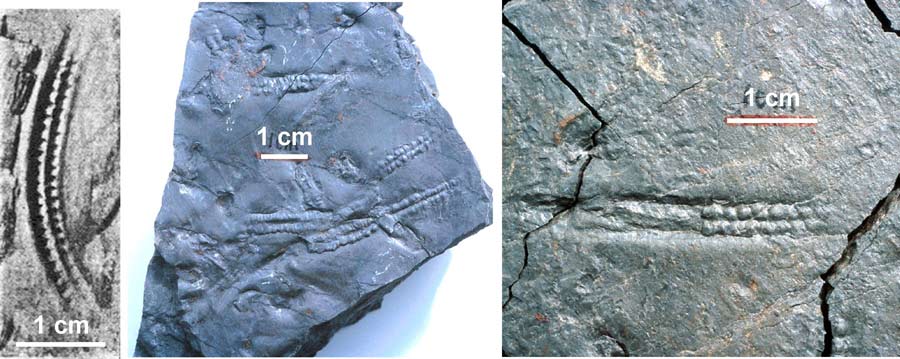

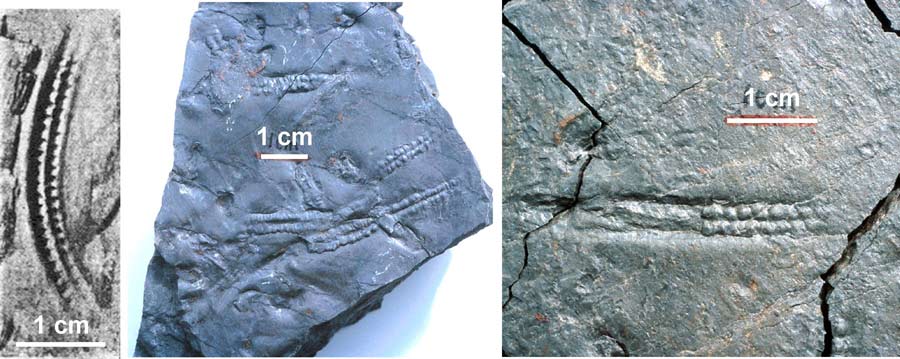

Examples of

Pteridichnites biseriatus, brittle star traces found in the Devonian Brallier Formation, collected along US 33 east of Elkins, WV (photo: R.R. McDowell)

The Acadian Orogeny, with its main uplift located northeast of West Virginia, occurred during the Middle and Late Devonian and resulted in an additional source of predominantly clastic marine deposits. However, near the end of the Devonian, the sea covering West Virginia retreated westward relatively rapidly, and the continental red beds of the Hampshire Formation were deposited over most of West Virginia.

The sea made one last major intrusion into West Virginia during the Middle Mississippian, resulting in the deposition of the Greenbrier Group, a series of predominantly limestone units. At the close of the Mississippian, West Virginia was essentially a land area undergoing erosion. A prominent unconformity marks the boundary between the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian subperiods of the Carboniferous Period in most of the Appalachian region, including West Virginia. This unconformity, known as the mid-Carboniferous eustatic event, is attributed to a drop in sea level (Blake and Beuthin, 2008).

Early in the succeeding Pennsylvanian Period, the land surface dropped to around sea level, and for more than 50 million years continued to subside at roughly the same rate sediments were being deposited on top of it. Swamp conditions prevailed during this time, resulting in the deposition of thousands of feet of nonmarine sandstone and shale as well as the many important coal seams we know today. For more information on West Virginia coal beds, please explore the links on the

WVGES Coal Bed Mapping Project (CBMP) page. Information on

trace elements in West Virginia coals is discussed on a separate web page.

The Appalachian Orogeny, a period of mountain building resulting from the collision of what is now North America with what is now Africa, peaked roughly 290 million years ago during the late Pennsylvanian. During that time, West Virginia was uplifted, sediment deposition ceased, and erosion began. A great deal of folding and thrust faulting occurred, especially in the eastern part of West Virginia. This orogeny played a major part in the formation of the Appalachian Mountains as we know them today.

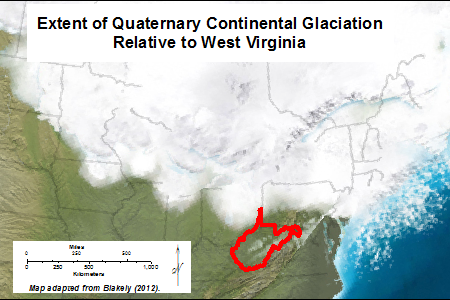

Quaternary Glaciation in the northeastern U.S.

(adapted from Blakey, 2012)

No sedimentary rocks from the Mesozoic Era are present in West Virginia. In other parts of the U.S. and the world, rocks of this age contain the remains of countless species of dinosaurs and other reptiles. Unfortunately, no such fossils are preserved in our state. During the early part of the era, considerable igneous activity took place in neighboring states to the east. A few dikes of gabbro and other mafic rock from the Jurassic Period, are present in Pendleton County, West Virginia and nearby counties in Virginia.

During the Cenozoic Era, igneous activity was renewed in the eastern part of West Virginia. Approximately 45 million years ago during the Eocene Epoch, a complex of dikes and sills with compositions ranging from basalt to rhyolite were intruded into the Paleozoic sedimentary rocks in the area in and around Pendleton County. These igneous rocks are some of the youngest in eastern North America. Tso and others (2004) discuss these unusual rocks in detail.

Late in the Cenozoic Era, during the Pleistocene Epoch of the Quaternary Period, glaciers covered the northern part of the North American continent, extending into Ohio and Pennsylvania, stopping just north of West Virginia. Prior to the advance of these ice sheets, drainage of the Monongahela River was northward to the St. Lawrence River system. An ice sheet created a dam near Pittsburgh, forming a lake that extended as far south as Weston, West Virginia. Drainage was diverted westward into the Ohio River system. Divergence of the New River system that formerly drained to the northwest created similar deposits in the preglacial Teays River system (which included what is now the New, Gauley, and Kanawha rivers). The Teays was dammed by ice near Chillicothe, Ohio, forming Lake Tight, sometimes called Lake Teays. Stream capture of the Teays, likely from the Kanawha River, left an abandoned river valley still visible today between the Charleston area and Huntington, now occupied by Interstate 64. Lake deposits, predominantly clay, were deposited in the Monongahela and Teays river basins. Please see

glaciation in West Virginia and

"Glacial" Lake Monongahela for more information. Except for recent alluvial deposits and the Eocene intrusives, there are no other known Cenozoic units in West Virginia.

MORE INFORMATION

WVGES has a treasure trove of information for earth-science teachers and anyone else interested in geology. Please consult our

GeoEducational Resources page for more information on basic geological principles, West Virginia geology, and tools for the classroom.

REFERENCES

-

Blake, B.M., Jr., and J.D. Beuthin, 2008, Deciphering the mid-Carboniferous eustatic event in the central Appalachian foreland basin, southern West Virginia, USA: in C.R. Fielding, T.D. Frank, and J.L. Isbell, eds., Resolving the Late Paleozoic Ice Age in Time and Space: Geological Society of America Special Paper 441, p. 249-260.

-

Blakey, R.C., 2012, Quaternary (Pleistocene), in The Cenozoic Timescale and Paleogeography, URL: ../cenozoic%20web/2/Timescale.html#2 accessed from ../cenozoic%20web/2/Timescale.html in December 2019.

-

Cardwell, D.H., 1975, Geologic History of West Virginia: West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey, Education Series ED-10, Morgantown, West Virginia, 69 p. [Please note: some of the information in this 1975 publication has been superceded.]

-

Scotese, C.R., 2001. Atlas of Earth History, Volume 1, Paleogeography, PALEOMAP Project, Arlington, Texas, 52 pp.

-

Scotese, C.R., 2002, PALEOMAP website: http://www.scotese.com, accessed April 2014.

-

Tso, J.L., R.R. McDowell, K.L. Avary, D.L. Matchen, and G.P. Wilkes, 2004, Middle Eocene Igneous Rocks in the Valley and Ridge of Virginia and West Virginia, Geology of the National Capital Region--Field Trip Guidebook (Trip 4), USGS Circular 1264: http://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/2004/1264/html/trip4/, accessed April 2014.

-

U.S. Geological Survey Geologic Names Committee, 2010, Divisions of geologic time—major chronostratigraphic and geochronologic units: U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 2010–3059, 2 p., URL: http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2010/3059/pdf/FS10-3059.pdf accessed April 2014.

Earth's landmasses and oceans in the Middle Ordovician

Earth's landmasses and oceans in the Middle Ordovician Examples of Pteridichnites biseriatus, brittle star traces found in the Devonian Brallier Formation, collected along US 33 east of Elkins, WV (photo: R.R. McDowell)

Examples of Pteridichnites biseriatus, brittle star traces found in the Devonian Brallier Formation, collected along US 33 east of Elkins, WV (photo: R.R. McDowell)

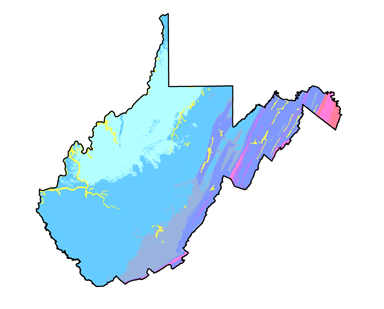

Simplified WV bedrock geology map

Simplified WV bedrock geology map WV Geological & Economic Survey

WV Geological & Economic Survey