How Do You Know What Kind of Rock You're Standing On?

A major part of the process of creating a geologic map is reconnaissance during which the geologist attempts to identify the rock unit or formation at each point visited on the map. This is usually a straightforward process when individual formations are well defined, each formation is distinctly different from its neighbors, and rock outcrops are well exposed. However, sometimes it is just not possible to attribute a particular outcrop to a single formation, especially when exposure is poor or limited in extent. In such an instance, the geologist sometimes resorts to using a proxy (a distinctive plant or animal or soil characteristic that commonly occurs in direct association with the rock in question) to help identify the rock itself. Shown above is an example of a plant proxy. Viper's Bugloss (Echium vulgare), known locally as blue thistle because of the sharp, siliceous spines present on the stem and leaves, is commonly found growing on shales such as the Devonian Needmore, Millboro, or Brallier. It is possible that the plant is attracted to the clay-rich soil that forms on top of this type of rock. When geologists see this plant growing in profusion in the Pendleton County area, they may suspect that the underlying bedrock is one of these shales.

Proxies also exist for carbonate rocks in the Pendleton County area. The Siluro-Devonian Helderberg Group, Silurian Tonoloway, and Wills Creek formations all weather to form soils rich in calcium carbonate and alkaline in nature. Shown below are examples of both plants and animals that may serve as proxies for these rock units.

On the left is a hilltop in eastern West Virginia covered with Northern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana var.). On the right are empty shells of two unidentified land snails. In both examples, the plant or animal prefers or requires soil developed on limestone bedrock. Red Cedars need alkaline soils to grow properly. Land snails require the mineral calcite (CaCO3) to form their shell. When geologists observe either of these two proxies, they know that the underlying bedrock contains carbonate rock.

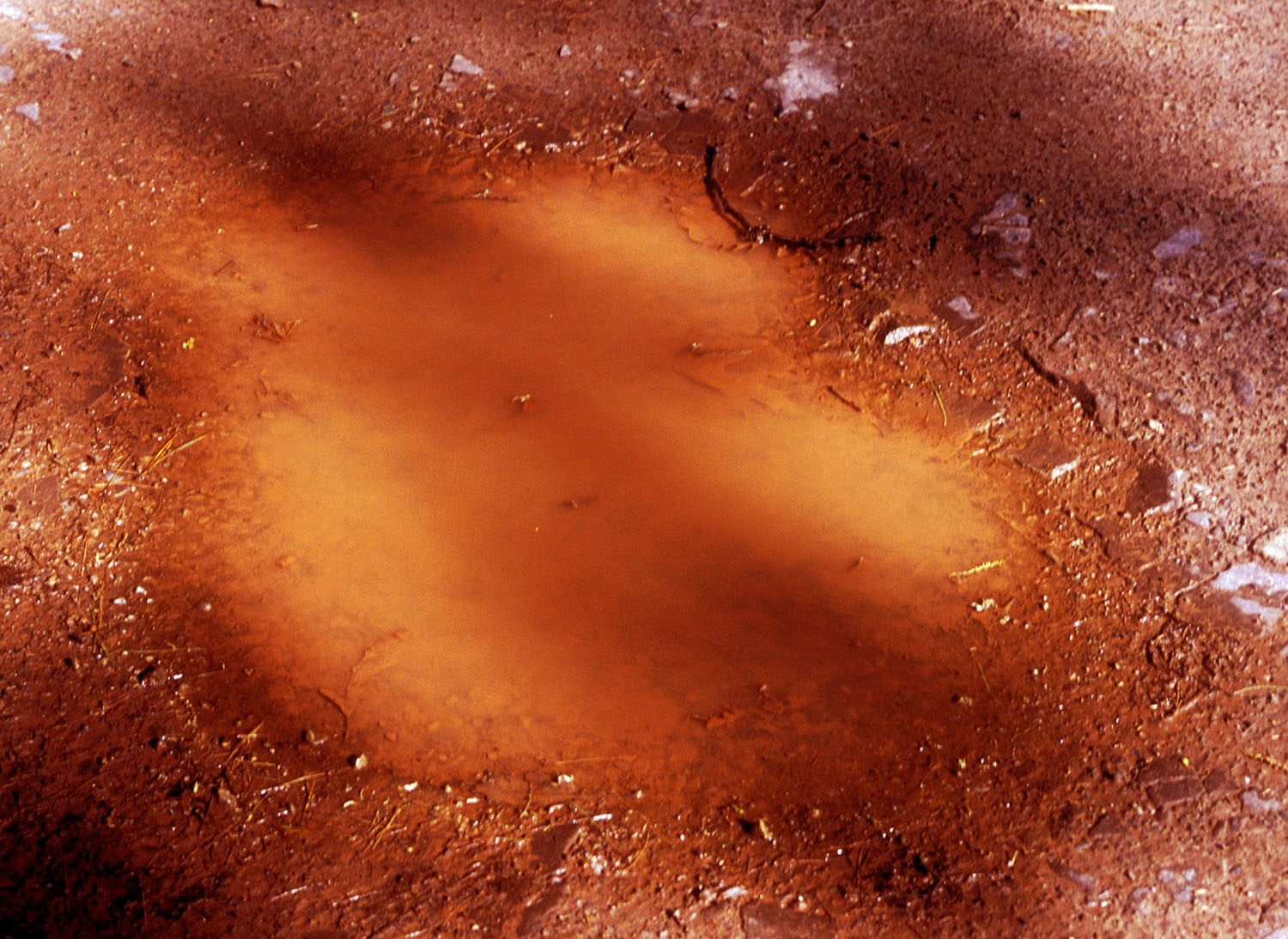

Sometimes, the identity of the near-surface bedrock can be obtained by noting simple details such as the color of the soil developed on the underlying rock unit. In the photo shown above, the color of the muddy water in the puddle indicates that the soil here is developed on one of the formations with dark red coloration due to the presence of oxidized iron. In this case, the soil, mud puddle, and bedrock are all associated with the Devonian Hampshire Formation exposed on Shenandoah Mountain, west of Criders, VA.

Page last revised May 2005

Page created and maintained by:

West Virginia Geological & Economic Survey

Address: Mont Chateau Research Center

1 Mont Chateau Road

Morgantown, WV 26508

Telephone: 1-800-WV-GEOLOgy (1-800-984-3656) or 304-594-2331

FAX: 304-594-2575

Hours: 8:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. EST, Monday - Friday

Permission to reproduce this material is granted if acknowledgment is given

to the West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey.