If you have a West Virginia geology question not addressed on our web site or in these "Frequently Asked Questions," please contact us at info@wvgs.wvnet.edu or (304) 594-2331.

West Virginia GeoFacts

Highest Point: Spruce Knob in the Circleville District of Pendleton County

Elevation: 4863 feet above mean sea level

Latitude: 38.699560, Longitude: -79.533090 (Degrees, NAD 1983)

Lowest Point: Harpers Ferry in the Harpers Ferry District of Jefferson County (the benchmark on the topographic map near the intersection of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers at Harpers Ferry indicates 287 feet, but it is situated above river level)

Elevation: approximately 250 feet above mean sea level, depending on Potomac River level

Latitude: 39.323217, Longitude: -77.728638 (Degrees, NAD 1983)

- Number of 7.5-minute (1:24,000-scale) topographic quadrangles covering the state: 496

- Number of 1:100,000-scale topographic quadrangles that cover the state: 27

- How to find specific topographic maps for a location: Use our interactive topo map index.

- Number of named coal seams in the State: 117

- Approximate number of minable coal seams in the State: 62

- Where to find coals seams for a certain location: Use our interactive coal maps. (Click on arrows next to Group to move down through the various seams.)

- Where to find mine locations: Use our interactive coal-mine map

Number of named oil and gas fields in the State: 393 (as of June 2017)

Deepest wells drilled in the state:

- Calhoun 2503 at 20,222', drilled in 1974 by Exxon USA

- Mingo 805 at 19,600', drilled in 1973 by Columbia Gas Transmission

- Lincoln 1469 at 19,124', drilled in 1974 by Exxon USA

- Number of counties with oil and gas wells: Wells have been drilled in 53 of the State's 55

counties. At this time, the only two counties with no oil or gas wells are Berkeley and Jefferson counties in the eastern panhandle.

State Rock: Bituminous Coal: The State rock (so designated by a House Concurrent Resolution, 37 in 2009) is bituminous coal. Coal is found naturally deposited in the vast

majority of the 55 counties of West Virginia. Coal was discovered in what is now West Virginia in 1742, by European explorer John Peter Salley in the area of Racine, West Virginia. Salley named the nearby tributary of the Kanawha River, where he observed the coal deposit, Coal River. In 1770, George Washington noted "a coal hill on fire" near West Columbia in what is currently Mason County. The first commercial coal mine was opened near Wheeling by Conrad Cotts in 1810, for blacksmithing and domestic use. The coal industry has been an integral part of the economic and social fabric of West Virginia.

Bituminous Coal

(

photographs by Ray Garton)

-

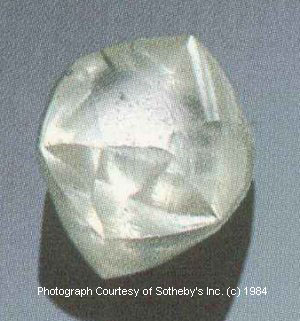

State Gem: Silicified Lithostrotionella, so designated by House Concurrent Resolution No. 39 adopted on March 10, 1990, is technically not a gemstone but the fossilized Late Mississippian coral Lithostrotionella, preserved by the siliceous mineral chalcedony. It is found in the Hillsdale Limestone of the Greenbrier Group in portions of Greenbrier and Pocahontas counties in West Virginia and is often cut and polished for jewelry or display.

Lithostrotionella and related corals lived about 340 million years ago during the Mississippian Period at a time when what is now West Virginia was covered by a shallow sea. In addition to corals, the Late Mississippian seas hosted a teeming fauna of brachiopods, trilobites, pelmatozoans, bryozoans, molluscs, and fish. There were two major types of Late Paleozoic corals: tabulate, such as Lithostrotionella and rugose. Both types were decimated in the great extinction at the end of the Permian Period, 245 million years ago, when an estimated 95% of the known species of life on earth vanished in a geologic instant. The resultant empty ecological niches were subsequently replaced by the scleractinian corals which form our reefs today.

Corals are generally colonial animals that excrete calcium carbonate (calcite) exoskeletons and frequently merge to form large colonies. Each individual animal, called a polyp, lives in its own small cup or recess. While adult polyps are sessile and live a stationary life, coral larvae are planktonic and are moved around by ocean currents. Polyps strain small particles of food from the water with their tentacles and retreat into the safety of the exoskeleton when threatened. Additionally, polyps host symbiotic algae called zooxanthellae within their tissues. These algae are nourished by the coral's waste products and in turn provide oxygen to the polyp via photosynthesis.

After the Lithostrotionella colony died, it became saturated with silica-rich water and the calcium carbonate in the exoskeleton was gradually replaced by the mineral chalcedony, a variety of microcrystalline quartz. West Virginia fossil corals are found in several colors, including light to dark bluish gray, pink, and red. Usually white to bluish gray in color, the unusual pink and red chalcedony in West Virginia's Lithostrotionella comes from trace concentrations of metals such as iron or manganese. Modern living corals get their variety of colors from zooxanthellae algae.

Note: Sando (1983) suggested the type species of Lithostrotionella is most likely a species of Acrocyathus and assigned the name Acrocyathus floriformis hemisphaericus to West Virginia specimens. For the state "gemstone," West Virginia still uses the name Lithostrotionella.

References

Garton, Ray, 2019, personal communication.

Sando, W.J., 1983, Revision of Lithostrotionella (Coelenterata, Rugosa) from the Carboniferous and Permian: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1247, 52 p., doi: https://doi.org/10.3133/pp1247.

State of West Virginia, 1990, Journal of the House of Delegates, sixty-ninth Legislature of West Virginia, Vol. 1 pp 791-792.

-

Lithostrotionella

Above:

Lithostrotionella, unaltered

Below:

Lithostrotionella, cut and polished

(

photographs by Ray Garton)

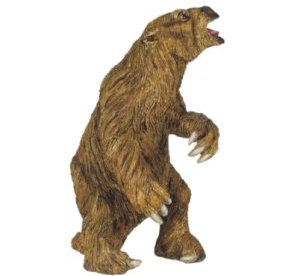

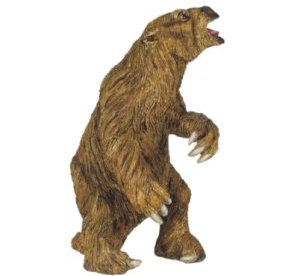

- State Fossil: Megalonyx jeffersonii: The State fossil (so designated by House Concurrent Resolution, 28 in 2008) is the extinct Pleistocene ground sloth Megalonyx jeffersonii. A left arm and hand were found in a Monroe County cave in the 1790's and scientifically described by Thomas Jefferson in 1797. The new species was named in honor of Jefferson by Caspar Wistar. One of the bones was Carbon-14 dated at 35,960 years.

-

Jefferson Ground Sloth Megalonyx jeffersonii

model

skull

skeleton

claws

sloth hand beside human hand

(model, skeleton, skull, and hand photographs by Ray Garton; claws by Ray Strawser)

- State Soil: Monongahela Silt Loam: The State soil (so designated by House Concurrent Resolution, 10 in 1997) is the Monongahela Silt Loam. Monongahela soils cover more than 100,000

acres in 45 counties in West Virginia. These soils are very deep, moderately well drained and occur on alluvial stream terraces that do not flood. Monongahela soils are used extensively for cultivation of crops, pasture, woodlands, hay, and home/building site development. Considered prime farmland, Monongahela soils generally have slopes of 3 percent or less. Find out more about the Monongahela Silt Loam from the West Virginia Association of Professional Soil Scientists. Recent West Virginia soil surveys are on the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) West Virginia Soil Surveys page, and the older booklet-style soil surveys are on the archived soils surveys page.

For more information on West Virginia, please see the West Virginia Encyclopedia.

Oil and Gas

- Where can I find natural gas-production data?

- WVGES maintains a large database of oil and gas well information on our Pipeline-plus and pipeline pages. The West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (WVDEP) also maintains information on petroleum wells and production on their WVDEP Database and Map Information page, and the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) has overall West Virginia natural gas-production data on the EIA Natural Gas data page.

- Where can I find information on oil and gas in my county?

What oil and gas fields are located in my area?

What formations produce gas and/or oil in my area?

- To answer all of these questions, WVGES maintains a large database of oil and gas well information accessible through our Pipeline-plus and pipeline pages, including an interactive map (opens as a separate page). The Department of Environmental Protection (WVDEP) also maintains detailed information on oil and gas wells on their WVDEP Database and Map Information page. On our Publications Sales Main Search page you can enter "oil gas" into the keywords box to generate a list of our oil and gas publications. The Atlas of Major Appalachian Gas Plays (Survey Volume V-25), is an invaluable resource for oil and gas information in West Virginia and the Appalachian Basin.

- Do you have a record of the old gas well near my house?

- WVGES has records for more than 150,000 wells drilled in the state. Approximately half of those have been drilled since permitting became required in 1929. We likely have some information for wells drilled prior to 1929, although this information may not be complete. Many, but not all, of the old records have been scanned. Data can be accessed through our Pipeline-plus page, pipeline page, and interactive map. Scanned files are available through the Pipeline-plus page. The Department of Environmental Protection (WVDEP) also maintains detailed information on oil and gas wells on their WVDEP Database and Map Information page. We may have some information on wells drilled prior to permitting, although this information may not be complete. Please contact us at info@wvgs.wvnet.edu or (304) 594-2331 if you need more information.

- Do you have well production records?

- Production reporting became required in 1979. The Survey has monthly and annual production data for most wells since then and they can be accessed through our Pipeline-plus and pipeline pages. Information on specific wells can be obtained from our Pipeline-plus Oil and Gas Well Header Data Search. The Department of Environmental Protection (WVDEP) also maintains detailed information on oil and gas wells on their WVDEP Database and Map Information page. Please contact us at info@wvgs.wvnet.edu or (304) 594-2331 if you need more information.

- Where can I find more information about the Marcellus Shale and other Devonian shales?

- We have an entire page devoted to information on the Marcellus and other Devonian Shales, including maps, data files, and nomenclature.

- What is the Utica Shale and where can I find more information?

- Despite its name, the Utica shale play is neither Utica nor shale. The actual drilling target is the Middle Ordovician subsurface unit informally called the Point Pleasant, a previously unnamed target in West Virginia. It is located stratigraphically near the Utica, a unit already known in West Virginia, and hence the term. The Point Pleasant consists of alternating thin beds of limestone and organic shale. The thin beds and lack of permeability created an exceptional trapping mechanism for gas generated as the reservoir matured. We should note that the names "Utica" and "Point Pleasant" are considered drillers' terms rather than names of formal stratigraphic units. A generalized stratigraphic column or strat chart for West Virginia shows the Formation and Group names along with drillers' terms and geologic time periods. WVGES worked in cooperation with several other partners to produce the Utica Play Book page, an extensive web site full of maps, various datasets, downloads, and reports, including a detailed final report The Utica Play Book

(PDF, 25.5 MB; 205 pages), devoted to Utica - Point Pleasant geology and production.

(PDF, 25.5 MB; 205 pages), devoted to Utica - Point Pleasant geology and production.

- What is the Rogersville Shale?

- The Rogersville Shale is an organic-rich unit in the Middle Cambrian Conasauga Group / Elbrook Formation. Located in the Rome Trough, it is older and deeper than the Marcellus and Utica-Point Pleasant. More information is on our Posters and Presentations page. A generalized stratigraphic column or strat chart for West Virginia shows the Formation and Group names along with drillers' terms and geologic time periods.

- What information do you have on the Trenton - Black River carbonates?

- WVGES worked in partnership with several other agencies to produce an extensive web page on the Trenton and Black River Project.

- What information do you have on Tight Gas Reservoirs ?

- The Appalachian Basin Tight Gas Reservoirs Project contains data, maps, and reports generated from a collaborative project between the Pennsylvania Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey and WVGES, with funding from the Department of Energy's National Energy Technology Laboratory. The project examined "the Mississippian-Devonian Berea/Murrysville sandstone play and the Upper Devonian Venango, Bradford and Elk sandstone plays in Pennsylvania and West Virginia; and the 'Clinton'/Medina sandstone play in northwestern Pennsylvania. In addition, some data were collected on the Tuscarora Sandstone play in West Virginia, which is the lateral equivalent of the Medina Sandstone in Pennsylvania."

- How long has oil and gas been drilled in West Virginia? Where can I find some historical information about the

oil and gas industry in the State?

- We have seen published illustrations of drilling and production activity in the Burning Springs area of Wirt County from the late 1850s. Our page on the history of the development of

the oil and gas industry in West Virginia has more information. An

excellent resource on the history of the development of the industry in the State is the Survey's Petroleum and

Natural Gas, Precise Levels, a 1904 Survey publication (Volume 1A) by then-Director I.C. White, which also

describes the development of the tools used for drilling by the salt industry in the Kanawha Valley.

Also, David L. McKain and Bernard L. Allen wrote an interesting history of the oil and gas industry in West Virginia in their book Where It All Began - The Story of the People and Places Where the Oil and Gas Industry Began - West

Virginia and Southeastern Ohio. An 1865 map at the beginning of the book shows the location of a well noted as

"first oil found 1790" near the town of Elizabeth in Wirt County.

The Oil and Gas Museum at 119 Third Street in Parkersburg is open on Saturdays and Sundays, with weekday and evening hours available by appointment. Contact the museum at (304) 485-5446. And, don't forget the Oil and Gas Festival held annually in September in Sistersville in Tyler County.

- Where is the deepest well drilled in West Virginia?

- The deepest well was drilled in 1974 by Exxon USA in Calhoun County, to a depth of 20,222 feet, bottoming in the

Precambrian basement. The well, permit number 2503, was dry with a gas show in the Big Lime and oil shows in the Upper

Devonian shale and the Marcellus shale.

The longest measured depth we currently have for a horizontal well is 21,660 feet in the Utica-Point Pleasant for Marshall 1583. For the Marcellus the longest measured depth that we have recorded is 20,294 feet for Doddridge 6507. These are horizontal, not vertical, wells.

Wells drilled to the Precambrian basement are important to geologists because they provide a "view" of the complete

stratigraphic section of sedimentary rocks in a particular area, and they may provide information about the potential of a

variety of gas and/or oil reservoirs in the area.

| Deepest Wells in West Virginia |

| County |

Permit Number |

Total Footage |

Formation at Total Depth |

| Calhoun |

2503 |

20,222 feet deep |

Precambrian basement |

| Mingo |

805 |

19,600 feet deep |

Precambrian basement |

| Lincoln |

1469 |

19,124 feet deep |

Precambrian basement |

| Jackson |

1366 |

17,680 feet deep |

Precambrian basement |

| Marion |

244 |

17,111 feet deep |

Ordovician Beekmantown Formation |

| Marshall |

539 |

16,512 feet deep |

Cambrian Copper Ridge Dolomite |

| Hardy |

21 |

16,075 feet deep |

Cambro-Ordovician Rome Formation |

| Wayne |

1572 |

14,625 feet deep |

Precambrian basement |

| Preston |

86 |

14,594 feet deep |

Ordovician Black River Group |

| Hampshire |

12 |

13,999 feet deep |

Cambrian Elbrook Formation |

| Wood |

351 |

13,331 feet deep |

Precambrian basement |

| Wood |

756 |

13,266 feet deep |

Precambrian basement |

| Randolph |

103 |

13,121 feet deep |

Ordovician Trenton Group |

| Braxton |

2236 |

13,040 feet deep |

Ordovician Wellscreek Limestone |

| Pendleton |

6 |

13,001 feet deep |

Ordovician Trenton Group |

| Grant |

2 |

13,000 feet deep |

Ordovician Beekmantown Formation |

- What is the deepest occurrence of natural gas produced in West Virginia?

- The basement test well, Jackson 1366, produced gas from a Rome sand (Middle Cambrian age) at a depth of 14,358 feet for

about six months before mechanical problems forced the well to be plugged. Otherwise, the deepest sustained gas production has been reported from the Upper Ordovician Trenton and Black River carbonates in Roane County. The discovery well was drilled in 1999, and gas is produced from a depth of 10,271 feet. For more information on this and other recently permitted and drilled wells, see Recently-Permitted Trenton and Deeper Wells. We also have an extensive web page on the Trenton and Black River carbonates.

- What is the deepest occurrence of oil produced in West Virginia?

- In the mid-1980s, some oil was produced from the Balltown sand of Upper Devonian age at a depth of approximately 2,900 to 3,200 feet in the Belington field in southern Barbour County. Some oil was produced from Devonian shales in northwestern West Virginia around the same time. A few wells produced oil from the Devonian Oriskany Sandstone at depths between 4,800 and 5,100 feet, and three wells produced oil from the Silurian Newburg sand at a depth of 5,500 to 5,800 feet.

- What field produced the largest amount of gas?

- The Elk-Poca field in Jackson, Kanawha, and Putnam counties has produced more than 1 Tcf (trillion cubic feet) of natural gas from more than 1,000 wells since 1933.

- What field produced the largest amount of oil?

- The Salem-Wallace field in the north-central part of the State produced more than 41 million barrels of oil through 1960.

- What county has the most oil and/or gas wells?

- The Survey has records for nearly 13,000 wells drilled in Ritchie County. Other densely-drilled counties include

Doddridge, Harrison, Kanawha, Lewis, Pleasants, and Roane.

- Who is in charge of regulating drilling and production of oil and gas wells in the State?

- The West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection's Office of Oil and Gas has regulatory authority over oil and gas wells drilled and produced in the State.

- What are my rights as a surface owner?

- The West Virginia Surface Owners' Rights Organization can provide that information.

- Where can I get maps of well locations?

- We have an interactive oil and gas well map (opens as a separate page) for viewing well locations. The Survey also has a collection of 7.5-minute quadrangle-based maps showing well locations available for public viewing, but not copying, in our Oil and Gas Records Office. Please contact us at info@wvgs.wvnet.edu or (304) 594-2331 for information about the commercial availability of quadrangle maps showing well locations.

WV Geological & Economic Survey

WV Geological & Economic Survey